Documentary Photography: Humanity Through a Lens

Documentary photojournalism sounds self-explanatory; however, its definition carries more meaning and history than its name might suggest. The short answer would be “photography that records events with historical or social impact.” While it is journalism, unlike regular photojournalism, documentary photojournalism can have bias. Unlike in normal photojournalism where objectivity and presenting facts are essential, documentary photojournalism aims to evoke emotions and has a subjective element. It wants viewers to feel something because of the image, making it more artistic and, as they say, subjective, the opposite of objective.

The history of photojournalism dates back to the early days of the medium, with photographers such as Louis Daguerre documenting reality. However, true photojournalism is attributed to Carol Szathmari and Roger Fenton, who documented the Crimean War in the mid-19th century. During the American Civil War, Mathew Brady documented the war with permission from Abraham Lincoln, contributing to early war photography. The “Golden Age” of photojournalism was around 1930 with technological advancements, portable cameras, and the rise of magazines like LIFE. Robert Capa and Henri-Cartier Bresson were some of the most important photographers in this era. In the 1930s, documentary photography gained prominence, capturing the impact of the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl drought. However, WWII shifted the focus of documentary photography with figures like Robert Capa (again) and Margaret Bourke-White capturing some of the most iconic photographs. In 1947, Magnum Photographic Agency was founded to give photographers more creative freedom. This concludes with modern technology, highlighting the role of smartphones and citizen journalism, as shown by the 2005 London bombing coverage and the Chicago Tribune starting to hire iPhone freelance photographers in 2013.

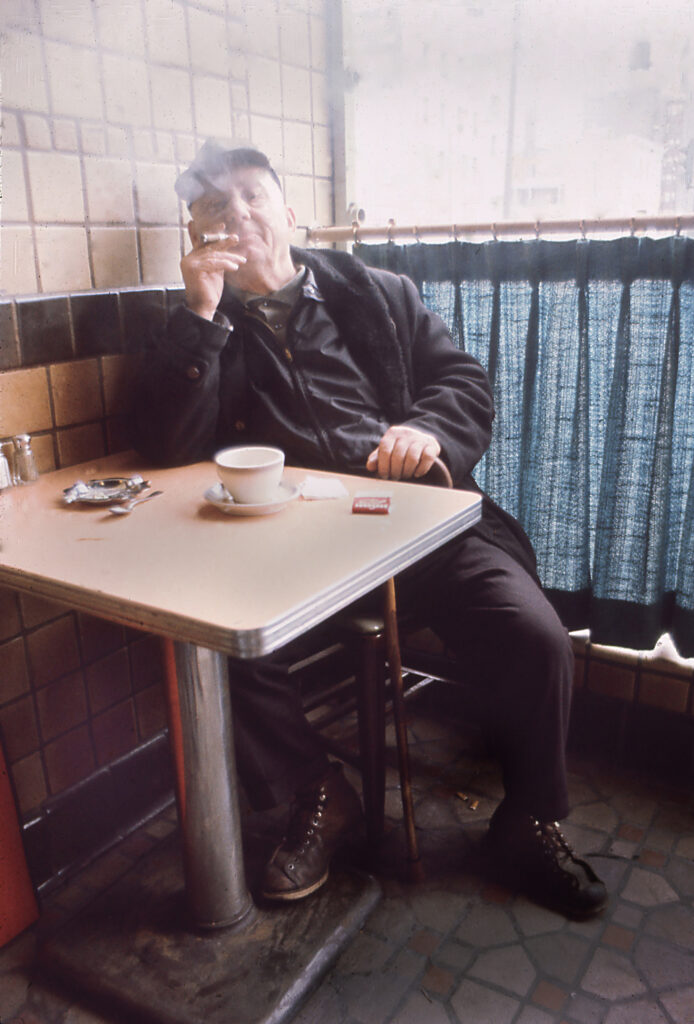

Documentary photography was created to show the world in a truthful and unfiltered way. Some of the most important photojournalism projects throughout history were “How the Other Half Lives” by Jacob Riis, “Street Life in London” by John Thomson, “Migrant Mother” by Dorothea Lange, “Born Free and Equal” by Ansel Adams, and “The Americans” by Robert Frank.

The Farm Security Administration (FSA) was created by Franklin Roosevelt between 1935 and 1943 to assist migrant farmers and sharecroppers as part of The New Deal. The FSA was founded in 1937, and the photographers in the FSA were named the “Historical Section” unit, taking on the largest photo documentary project in history at that time, producing nearly eighty thousand photos. In 1937, the RA and its Historical Section merged into the FSA, and Roy Stryker was chosen as the leader for the “Historical Section” unit. The FSA wasn’t a jobs program; photographers were hired based on their skill, and their assignments required extensive travel across the US, lasting for months most of the time.

In the late 1960s, the American landscape faced challenges including unchecked land development, urban decay, and pollution. To combat this, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) created a photo documentary project known as “DOCUMERICA” in 1971. The project aimed to document the environmental movement in the US from 1972 to 1978, resulting in twenty thousand photographs. The project faced challenges and was almost terminated due to its complexity, financial issues, and copyright claims. However, after a reorganization in 1972 under Arthur Rothstein, who previously worked on the FSA project, the DOCUMERICA movement gained momentum. The project became popular in the US and offers a visual record of the environmental evolution in the US throughout three decades. It captured images of resilience, humanitarian response, and resourcefulness in the face of social and environmental crises.

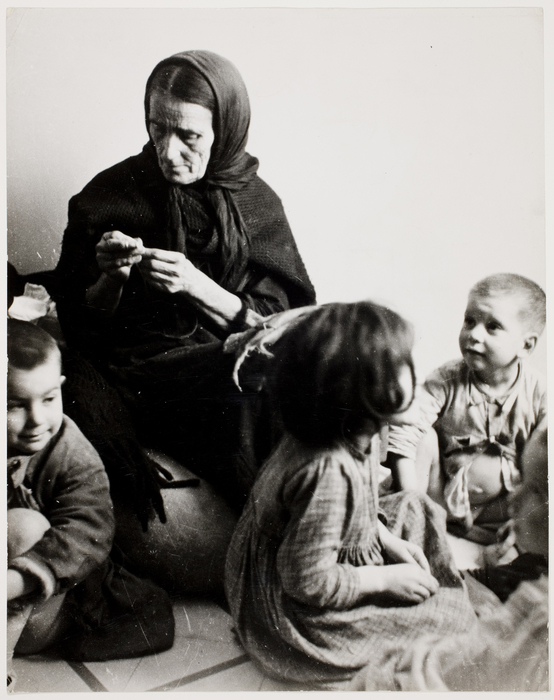

Lewis Hine was an American photographer born in Wisconsin whose photography aimed to bring attention to social issues in the US. Initially, he took photographs of immigrants arriving at Ellis Island in 1905, capturing the living and working conditions in tenements and sweatshops. In 1909, he published “Child Labor in the Carolinas” and “Day Laborers Before Their Time,” documenting child labor. These projects exposed the reality of children working in dangerous conditions, and Hine was later hired by the National Child Labor Committee to contribute to federal regulations on workplace conditions. During WWI, Hines worked with the Red Cross as a photographer, and after the war, he worked on “The Children’s Burden in the Balkans” in 1919. When he returned to New York, he documented the construction of the Empire State building, capturing images while hanging from cranes to get specific angles. He published his works in 1932 as “Men at Work.” Throughout the years, he continued to work with the government on photo documentary projects. His work is a powerful testament to the impact of photography in raising awareness in the fight for social justice.

Documentary photography serves various purposes and contributes to visual storytelling, education, advocacy, and historical documentation. Some common uses and places where documentary photography can be found include galleries, exhibitions, books, news, educational materials, museums, social media, documentary films, amongst many others.